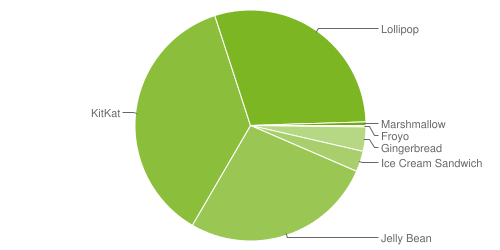

Google can remotely reset phones running versions older than Android 5.0, a report by the New York District Attorney’s office says, highlighting how investigators could easily obtain data. Seventy-four percent of all Android gadgets appear to be vulnerable.

| Version | Codename | API | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.2 | Froyo | 8 | 0.2% |

| 2.3.3 – 2.3.7 |

Gingerbread | 10 | 3.4% |

| 4.0.3 – 4.0.4 |

Ice Cream Sandwich | 15 | 2.9% |

| 4.1.x | Jelly Bean | 16 | 10.0% |

| 4.2.x | 17 | 13.0% | |

| 4.3 | 18 | 3.9% | |

| 4.4 | KitKat | 19 | 36.6% |

| 5.0 | Lollipop | 21 | 16.3% |

| 5.1 | 22 | 13.2% | |

| 6.0 | Marshmallow | 23 | 0.5% |

Data collected during a 7-day period ending on December 7, 2015.

Any versions with less than 0.1% distribution are not shown.

Data obtained from: Google

If Google receives a court order, they could potentially reset older versions of Androids that are locked using a pattern. Any devices running on Android 5.0 and newer won’t be accessed.

Here’s the catch: Encryption isn’t a mandatory setting in Android 5.0. Some manufacturers don’t enable it, even if it’s an option. In other words, the estimate of 74 percent could actually be low, meaning even more devices are open to remote resets. Luckily, in the case of Android 6.0 Marshmallow, all devices ship with encryption enabled, making them safe from prying eyes

The New York District Attorney’s office said that Google and Apple would have to unlock smartphones when presented with a court order. However, it would only be possible to do so without the owner’s permission with unencrypted phones.

Good Job Google and Apple others should follow your example. These are good foundations and starting points to ensure the privacy and security of your customers all around the world.

If you want some extra security on your android and ios devices you should check this article:

PRIVACY AND SECURITY – FACE VIBER AND BBM NOT QUITE SECURE TOR AND OPEN WHISPER CHAMPIONS OF SECURITY

Since Apple enabled encryption by default in September 2014 with their iOS 8, they can’t access any data on devices without knowing the user’s passcode. Apple can’t remotely bypass passcodes on devices running on iOS 8 or higher.

Apple statement:

Encryption

“On devices running iOS 8, your personal data such as photos, messages (including attachments), email, contacts, call history, iTunes content, notes, and reminders is placed under the protection of your passcode,” the company wrote on its website Wednesday evening. “Unlike our competitors, Apple cannot bypass your passcode and therefore cannot access this data. So it’s not technically feasible for us to respond to government warrants for the extraction of this data from devices in their possession running iOS 8.”

Apple did not immediately respond to requests for further comment.

In an open letter also published Wednesday, Apple CEO Tim Cook took a direct swipe at Google, its primary mobile competitor.

“Our business model is very straightforward: We sell great products. We don’t build a profile based on your email content or web browsing habits to sell to advertisers,” he wrote. “We don’t ‘monetize’ the information you store on your iPhone or in iCloud. And we don’t read your email or your messages to get information to market to you. Our software and services are designed to make our devices better. Plain and simple.”

The specific technical changes seem to be outlined in a new 43-page document entitled “iOS Security Guide September 2014,” the company’s perfunctory list of changes for each new version of iOS. The previous version of this document, dated February 2014, referred to the company’s hardware-based proprietary file and keychain protection mechanism called Data Protection, which uses 256-bit AES key and then encrypts every new file created.

Previously, Apple only mentioned one specific company-made app—Mail—that was protected using this system, while noting that “third-party apps installed on iOS 7 or later receive this protection automatically.”

Now, however, that section of the September 2014 document specifically refers to Messages, Mail, Calendar, Contacts, and Photos, which suggests that Apple has significantly expanded what data on the phone is encrypted.

Much of the subsequent language in the two documents is nearly identical in both versions:

By setting up a device passcode, the user automatically enables Data Protection. iOS supports four-digit and arbitrary-length alphanumeric passcodes. In addition to unlocking the device, a passcode provides entropy for certain encryption keys. This means an attacker in possession of a device can’t get access to data in specific protection classes without the passcode.

The passcode is entangled with the device’s UID, so brute-force attempts must be performed on the device under attack. A large iteration count is used to make each attempt slower. The iteration count is calibrated so that one attempt takes approximately 80 milliseconds. This means it would take more than 51⁄2 years to try all combinations of a six-character alphanumeric passcode with lowercase letters and numbers.

There are a few other privacy-minded changes as well.

The September 2014 document also notes that iOS 8 includes an “Always-on VPN” feature, which “eliminates the need for users to turn on VPN to enable protection when connecting to Wi-Fi networks.”

It also mentions that when an iOS 8 device is not associated with a Wi-Fi network, and the processor is asleep, the device uses a randomized Media Access Control address.

And with iOS 9 protection goes further

Apple set up a new two-factor authentication system and updated its passcode requirements for iOS 9. These changes make it harder for someone else to access or steal user data stored on iPhones and iPads.

Stronger passcodes for better security

It seems like a minor change, but Apple changing its passcode requirements to six digits instead of the more common four digits significantly boosts security for iOS 9 devices.

This means attackers now have to try 1 million possible combinations versus the previous set of 10,000 in order to break into the user’s iPhone and iPad. A four-digit passcode is very easy to crack, especially since users tend to use repeating numbers (1111, 2222, and so on), sequences (1234), or other common combinations (2580). Researchers recently came up with an automated cracking system that could break the four-digit codes in anywhere from 6 seconds to 17 hours.

Adding two digits to the passcode makes it much harder to crack, requiring up to several months of effort. In fact, a strong six-digit alphanumeric passcode can take 196 years to crack, according to the iOS Hacker’s Handbook.

But all that is merely theoretical, because after 10 failed attempts, an iOS 9 device will erase itself.

Google statement :

“Google has no ability to facilitate unlocking any device that has been protected with a PIN, password, or fingerprint. This is the case whether or not the device is encrypted, and for all versions of Android,”

SO KEEP YOUR PASSWORD SAFE AND ONLY IN YOUR MIND You do not have nothing to hide OK but it is your basic HUMAN RIGHT to protect your privacy as you think fit nevertheless you only keep your cooking recipes on your storage.

Google revealed that encryption would be mandatory in a recent Android Compatibility Definition Document. The compatibility document describes various elements of Android 6.0 and defines how it is intended to run on a variety of devices. Those devices that support full-disk encryption and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) crypto performance above 50MiB/sec, full-disk encryption must have this feature enabled by default. Full-disk encryption utilizes a key for all data that is stored from the disk. Data must pass through the key and be encrypted or decrypted before any data can be either written or pulled into system processes.

Google released Compatibility requirements for Android 6.0 (also known as Marshmallow), and there’s one new requirement that is justifiably getting a lot of attention – full-disk encryption must be enabled by default.

If the devices meet or exceed certain memory and performance figures, at any rate. (In other words, budget devices may still end up unencrypted.)

Google says encryption must be turned on by default, meaning devices are encrypted when a consumer has completed out-of-the-box setup:

For device implementations supporting full-disk encryption and with Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) crypto performance above 50MiB/sec, the full-disk encryption MUST be enabled by default at the time the user has completed the out-of-box setup experience.

You might remember that, last September, a Google spokeswoman declared that encryption would be enabled by default in all Android devices running Android 5.0 (Lollipop).

At the time, Google’s Android had fallen behind Apple’s iOS in data protection – iOS 8 had just been released, with encryption turned on by default.

The announcements that both Android and iOS devices would have default encryption kicked off a spat about encryption backdoors between Google, Apple and the law enforcement community that has been going on ever since.

Well, Google’s promise of default encryption in Lollipop devices didn’t come to fruition, and the ‘requirement’ for device makers to turn on encryption at setup was changed last March to a ‘strong recommendation’.

The problem, Google said, was poor performance on many devices.

Now that default encryption is once again being described by Google as a MUST for device manufacturers, it seems like the pro-encryption crowd can claim another victory.

Sort of.

Along with devices that have insufficient cryptographic performance, devices that were launched with earlier versions of Android are also exempted when upgrading to version 6.0:

If a device implementation is already launched on an earlier Android version with full-disk encryption disabled by default, such a device cannot meet the requirement through a system software update and thus MAY be exempted.

Devices without a lock screen are also exempt (such as wearables), because a device is encrypted when you set up a lock screen with a passcode, which is used to generate the encryption key.

Even if you don’t set up a lock screen with a passcode out of the box, encryption will still be set up with a default passcode.

Google also says device makers must not send the encryption key off the device, which means no one – not law enforcement, not a crook who nabs your phone, and not even Google – can decrypt your device without your passcode

And with Android Marshmallow 6.0 + protection goes further

Android Marshmallow security

App permissions

This is one of the unsexy but incredibly important parts of Android Marshmallow. The Android system now offers user-facing controls over some, but not all, app permissions. While iOS has had this feature for years, Android is only now catching up. Some basic permissions – internet access, for example – are still granted by default, but generally speaking you will be asked to grant individual app permissions the first time an app attempts to access them.

This means you are in control of whether or not an app has access to something as critical as your microphone or camera. Some apps might not work properly with certain permissions disabled, but the onus is on the app developers to stabilize their apps without all permissions granted, not on you to accept what you might feel are unnecessary permissions.

Permissions for a particular app can be viewed within the settings menu (to which permissions an app does or doesn’t have) or by permission type (so you can see how many apps have access to your contacts, for example). Viewing by permission type is slightly hard to get to, but at least that will stop accidental changes from being made.

Fingerprint API

Android Marshmallow introduces system-level fingerprint support via the new fingerprint API. Both new Nexus devices have a fingerprint scanner. The rollout of Android Pay and other touchless payment systems that rely on fingerprint scanners for authentication can now be handled by Android itself rather than a manufacturer add-on. Fortunately, Google has set minimum standards for scanner accuracy in order to pass its device certification.

Update: We’ve been very impressed with Nexus Imprint on the Nexus 5X and Nexus 6P, partially for the excellent Huawei hardware but also for Google’s implementation of the software. Registering a fingerprint is faster than on any other device and the accuracy and speed of the scanner is second to none. All you need to do to set up fingerprint authentication in the Play Store for purchases is check a box in the settings.

Automatic app backup

Historically, Android has offered a pretty weak app backup solution. The Backup and reset section in Lollipop was opt-in, vague and incomplete. Marshmallow can now automatically back up both your apps and data, so any apps restored from a backup will be the same as they were before – you’ll be signed in and right where you left off.

The explanations are much clearer in Marshmallow too and you can choose to opt out if you like (not everyone will be a fan of having their app data stored in the cloud, despite its convenience). The best part is that device and app data can be saved, so your passwords, settings and progress can all be restored with much less effort.

Network security reset

Network security reset is a nice little feature in the Backup and reset settings which allows you to quickly and easily remove all passwords, settings and connections associated with Bluetooth, cellular data and Wi-Fi. It’s a simple addition that demonstrates how much attention to enhanced security and user-facing controls in Marshmallow.

Monthly security patches

Following the Stagefright scare, Google and a number of manufacturers pledged to provide monthly security updates to keep on top of any security weaknesses in Android. With this in mind, Marshmallow now displays your device’s Android security patch level section in the About phone section.

Encryption

Encryption is back in Android Marshmallow with a vengeance. Encryption was a big deal in Android Lollipop too – and came as default on the Nexus 6 and Nexus 9 – not as many Android devices as Google would have liked had disk encryption forced on them, because of performance issues (encryption slows system performance down unless a hardware accelerator is used).

Marshmallow heralds the dawn of the new age of Android encryption, although only on new devices. New Android devices running Marshmallow are required to use full-disk encryption by default, but devices updated from a previous version of Android do not.

Devices with minimal processing power are also exempt, as are devices without a lock screen, such as Android Wear watches. Encrypted devices will also be subject to Marshmallow’s verified boot process to ensure the trustworthiness of their software during each boot sequence. If Android suspects changes have been made, the user will be alerted to potential software corruption.

Android for Work

Android Marshmallow is also pushing the enterprise angle with sandboxing for Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) environments. Through better handling of security, notifications, VPNs, access and storage, the same device can be used both for work and at home. It’s not a very sexy addition, but it means fewer people will be required to carry a personal and a work phone in future.

Smart Lock

Smart Lock has been around since Lollipop, but it bears repeating now that smartwatches are more prevalent. Smart Lock on Marshmallow provides options for unlocking your device or keeping your device unlocked depending on various intuitive scenarios. Smart Lock is found in the security settings and requires the use of some form of lock screen security.

Smart Lock includes options for trusted devices (for example, paired smartwatches or Bluetooth speakers), trusted places (home or office, via GPS and Wi-Fi data), trusted faces and on-body detection. The last of these won’t lock your phone again until you put it down. Each Smart Lock feature is opt-in and reversible.

Smart Lock for Passwords

Google’s old Google Settings app is no more, having graduated to its very own section in the Settings menu, where it belongs. This area contains all your Google settings and preferences. Everything from Voice, Google Fit, Now and location access is contained here, so it’s worth getting to know this area.

One new addition is called Smart Lock for Passwords and it is basically a Google password manager. Enabling the feature allows your website and app passwords to be saved to your Google account (which is why it lives in the Google section and not the Security section of Marshmallow). You can also exclude apps or view your Smart Lock for Passwords content.

NSA FBI and others from security community strongly against data encryption

Along with iOS 8, Apple made some landmark privacy improvements to your devices, which Google matched with its Android platform only hours later. Your smartphone will soon be encrypted by default, and Apple or Google claim they will not be able open it for anyone – law enforcement, the FBI and possibly the NSA – even if they wanted to.

Predictably, the US government and police officials are in the midst of amisleading PR offensive to try to scare Americans into believing encrypted cellphones are somehow a bad thing, rather than a huge victory for everyone’s privacy and security in a post-Snowden era. Leading the charge is FBI director James Comey, who spoke to reporters late last week about the supposed “dangers” of giving iPhone and Android users more control over their phones. But as usual, it’s sometimes difficult to find the truth inside government statements unless you parse their language extremely carefully. So let’s look at Comey’s statements, line-by-line.

Comey began:

I am a huge believer in the rule of law, but I also believe that no one in this country is beyond the law. … What concerns me about this is companies marketing something expressly to allow people to place themselves beyond the law.

First of all, despite the FBI director’s implication, what Apple and Google have done is perfectly legal, and they are under no obligation under the “the rule of law” to decrypt users’ data if the company itself cannot access your stuff. From47 U.S. Code § 1002 (emphasis mine):

A telecommunications carrier shall not be responsible for decrypting, or ensuring the government’s ability to decrypt, any communication encrypted by a subscriber or customer, unless the encryption was provided by the carrier andthe carrier possesses the information necessary to decrypt the communication.

Comey continued:

I like and believe very much that we should have to obtain a warrant from an independent judge to be able to take the content of anyone’s closet or their smart phone.

That’s funny, because literally four months ago, the United States government was saying the exact opposite before the US supreme court, arguing that, in fact, the feds shouldn’t need to get a warrant to get inside anyone’s smartphone after you’re arrested. In its landmark June ruling in the case, Riley v California, the court disagreed. So it’s great to see that Jim Comey, too, has come around to the common sense conclusion that cops need a warrant to search your cellphone data, but it would’ve been nice for him to express those sentiments when they actually mattered.

On Thursday, Comey went on to argue:

The notion that someone would market a closet that could never be opened – even if it involves a case involving a child kidnapper and a court order – to me does not make any sense.

This idea – that the police won’t be able to get a hold of anyone’s cellphone data and will soon be facing some unstoppable crimewave of body-snatching proportions – borders on absurd. As the Intercept’s Micah Lee has documented, the feds still have myriad ways to access everyone’s data. They can still get a warrant for iPhone users iCloud accounts, which hundreds of millions of people use to back up their phones and was central to a celebrity hacking scandal that’s been in the headlines for weeks. The feds can still go to the phone carriers to track anyone’s location 24/7, get all the metadata they want from text messages, and wiretap your phone calls. And even if none of these techniques work, depending on the strength of the person’s password, the cops may be able to crack a phone’s encryption passcode within minutes.

Comey concluded:

I get that the post-Snowden world has started an understandable pendulum swing. … What I’m worried about is, this is an indication to us as a country and as a people that, boy, maybe that pendulum swung too far.

This might be a good time to point out that Congress has not changed surveillance law at all in the the nearly 16 months since Edward Snowden’s disclosures began, mostly because of the vociferous opposition from intelligence agencies and cops.

IF YOU WANT SOME EXTRA SECURITY THAT CAN PROTECT YOU FURTHER FROM THE EYES OF YOUR OWN PHONE AND INTERNET PROVIDER PLEASE READ THIS ARTICLE

Apparently NSA doesn’t learn from the past and still makes the same mistakes

PRIVACY AND SECURITY – FACE VIBER AND BBM NOT QUITE SECURE TOR AND OPEN WHISPER CHAMPIONS OF SECURITY

Apple has come out twice—guns a-blazing—against efforts by law enforcement agencies to weaken public-key encryption in the name of national security.

The issue came up in the 60 Minutes interview with Apple CEO Tim Cook that aired Sunday, and it surfaced again Monday when the company filed an eight-page brief opposing Britain’s Investigatory Powers Bill—the so-called “snooper charter.”

The political winds may shift—for encryption when the NSA runs amok, against encryption when terrorists strike—but the crux of the matter never changes. It’s a matter of arithmetic.

The only way we know how to protect privacy, Cook told 60 Minutes‘ Charlie Rose, is with encryption.

Modern encryption, as former Apple executive Jean Louis Gassée explained last week in Let’s Outlaw Math, is based on a simple mathematical fact. It’s easy to calculate the product of two prime numbers, but going the other way—breaking a long number into its prime factors—gets exponentially harder the longer that number gets.

Public key encryption—the kind that ships in devices made by Apple AAPL -0.56% and Google AAPL -0.56% —is based on the difficulty of solving that math problem.

In one 2009 experiment, it took hundreds of computers two years to guess the prime factor of a single 232-digit number. Researchers estimated that a 1024-bit key would take 1,000 times longer.

The “backdoor key” police say they need to fight crime would have to somehow cut through thousands of years of number crunching without defeating that purpose. As Apple put it in its Monday submission to the British Parliament:

“A key left under the doormat would not just be there for the good guys. The bad guys would find it too.”

When politicians say we need backdoor keys for own protection, writes Gassée, “one is tempted to ask, glibly, if these leaders are ignorant, delusional, or dishonest—or all of the above.”

Apparently NSA has not learned anything from its past mistakes now they are compromising others data and themselves

Two “back doors” hidden in security software used by US government agencies and corporations that left them open to attack may have been caused by the NSA, security researchers claim.

Last week, news broke about “unauthorised code” in devices sold by Juniper, which builds firewalls, intended to protect the user from attacks and unwanted intrusions. Wired reports thatsecurity consultancy Comsecuris’ founder Ralf-Phillipp Weinmann’s research indicates that the NSA may be responsible for this — by introducing code that was exploitable by others.

Matthew Green, a cryptography lecturer at John Hopkins University, has come to a similar conclusion. In a blog post also outlining the scale of the vulnerability, he wrote:

To sum up, some hacker or group of hackers attacker noticed an existing backdoor in the Juniper software, which may have been intentional or unintentional — you be the judge! They then piggybacked on top of it to build a backdoor of their own, something they were able to do because all of the hard work had already been done for them. The end result was a period in which someone — maybe a foreign government — was able to decrypt Juniper traffic in the U.S. and around the world.

If correct, the NSA likely introduced this back door in order to give them a way to surreptitiously monitor traffic: It allowed them to decrypt otherwise-encrypted data, for a start. But someone else — we don’t yet know who — found it, and took advantage.

Edward Snowden reaction

“Technologists and companies working to protect ordinary citizens should be applauded, not sued or prosecuted,” Snowden wrote in an email through his lawyer.

He said that companies like Apple and Google might in certain cases be found legally liable for providing material aid to a terrorist organization because they provide encryption services to their users.

In his email, Snowden explained how law enforcement officials who are demanding that U.S. companies build some sort of window into unbreakable end-to-end encryption — he calls that an “insecurity mandate” — haven’t thought things through.

“The central problem with insecurity mandates has never been addressed by its proponents: if one government can demand access to private communications, all governments can,” Snowden wrote.

“No matter how good the reason, if the U.S. sets the precedent that Apple has to compromise the security of a customer in response to a piece of government paper, what can they do when the government is China and the customer is the Dalai Lama?”

Weakened encryption would only drive people away from the American technology industry, Snowden wrote. “Putting the most important driver of our economy in a position where they have to deal with the devil or lose access to international markets is public policy that makes us less competitive and less safe.”

Snowden entrusted his archive of secret documents revealing the NSA’s massive warrantless spying programs all over the world to journalists in 2013. Two of those journalists — Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras — are founding editors of The Intercept.

BEST SECURITY IS TO BE UPDATED ALWAYS ABOUT THESE MATTERS KNOWLEDGE IS PRICELESS and remember there are no bulletproof measures it is constant game of cat and mouse

Sources:

Apple Makes a Strong Case for Strong EncryptionResearchers think that a dangerous ‘back door’ in software used by the US government was caused by the NSA

Your iPhone is now encrypted. The FBI says it’ll help kidnappers. Who do you believe?

Apple gets serious about data security with iOS 9

New Android Marshmallow devices must have default encryption, Google says

Android 6.0 Marshmallow: all the key features explained

Apple expands data encryption under iOS 8, making handover to cops moot

Running an older Android OS version? Google can access your data

REPORT OF THE MANHATTAN DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE ON SMARTPHONE ENCRYPTION AND PUBLIC SAFETY

Google can bypass security on all Android systems that don’t use full-disk encryption

The most personal technology must also be the most private

Best Regards

TBU NEWS