(CNN) — Fifty years ago, a Frenchman and a German — seared by the devastation of World War II — forged an enterprise with the less than exciting name of the European Coal and Steel Community.

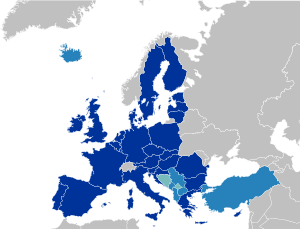

West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and French Prime Minister Robert Schuman’s modest beginning to European integration — to tie together the coal and steel industries of France, West Germany and the Benelux countries — would over the next half-century become a behemoth of 27 states, many of which didn’t even exist in 1952.

That European Union vision is now at an historic crossroads and could over the next months begin to shred.

The European club has both expanded in number and deepened in purpose. Beginning as a common market with expensive subsidies to farmers, it evolved into a community with coordinated foreign and trade policies, open borders among many members, a common social policy and a powerful European Court. Vast sums have been spent on infrastructure for poorer members.

Most notably, the Maastricht Treaty, named after the Dutch seaside town where it was signed in 1992, began the process of monetary union and — supposedly — economic convergence among member states. The first part happened; the second did not. A “stability and growth pact” was meant to harmonize interest rates, inflation and government deficits. But there were no enforcement mechanisms beyond sharp words and a slap on the wrist. France and Germany were among the first states to breach the commandment that deficits shalt not exceed 3% of GDP.

Some critics argue that Europe is like the python that swallowed a goat. In 1990, there were 12 members of the EU; now, the 27 members span an area from Lisbon to Talinn, from Cyprus to Stockholm.

How Europe grapples with the dysfunctional legacy of both an unbalanced deepening and headlong expansion will decide whether the eurozone recovers or withers.

The state of things now

The first hurdle to overcome is this weekend’s Greek elections. Should a working majority emerge under the leadership of the New Democracy Party, Greece may follow through with the next tranche of public spending cuts demanded by its “troika” of creditors: the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank. The new Greek government will expect in return help from the troika rather than the same diet of austerity, arguing that the Greek people have to be offered some incentive to endure more sacrifice.

But if this weekend’s election extends the political paralysis begun by May’s vote, the uncertainty over whether Greece can remain in the eurozone will intensify. Should the left-wing Syriza party emerge as the largest, with its commitment to tear up the current bailout agreement, markets will begin to anticipate a “disorderly exit” from the eurozone.

Even if a weak pro-bailout government is formed, Greece is already behind on its obligations to privatize state industries and improve tax receipts. For Greeks, tax evasion is a national sport; the government is owed nearly 50 billion euros in back taxes. Greek media suggest depositors have withdrawn up to 5 billion euros from local banks in the past two weeks.

Uncertainty in Greece would in turn intensify the pressure on Spain and Italy, amid doubts about the whole eurozone enterprise. The combined economies of Ireland, Portugal and Greece — the three countries that have been bailed out — are smaller than that of Spain, which has quickly been dubbed “too big to bail, too big to fail.” The European Union’s willingness to help bail out Spain’s massively indebted banking system to the tune of 100 billion euros ($125 billion) produced a “relief rally” on the bond and stock markets, but the relief scarcely lasted 24 hours.

By the end of the week, the yield on Spain’s 10-year bond hovered around 7%, the financial equivalent of being admitted to intensive care with a raging fever. The new Spanish government has resisted a full bailout, arguing that it has undertaken drastic economic reform and that government finances (not too awful) should not be confused with the banks’ (dreadful). But the influential ratings agencies do see a link; Moody’s has cut Spanish sovereign debt to just a notch above junk status, on a par with Azerbaijan. Unemployment is at record highs, especially among the young; house prices are collapsing.

The Italians are also getting fed up with austerity, as Prime Minister Mario Monti acknowledged in a recent interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour. He has joined the “growth club” with new French President Francois Hollande but has precious little room for maneuver, as the price on Italian debt has also risen. The IMF has praised Monti’s efforts to sort out Italy’s public finances but says deregulation and labor reform require further effort, just as the Italian economy is forecast to shrink 2% this year.

From outside the eurozone, its partners look on with horror. The governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, said last month, “Our biggest trading partner is tearing itself apart with no obvious solution.”

What will be Europe’s future?

Going forward (and, admittedly, simplifying the scenarios), Europe is looking at three paths, according to political and financial analysts.

The first and most traumatic is a disorderly collapse of the eurozone, starting in Greece but spreading to Spain and Italy. This scenario begins with anything less than a clear victory for the “bailout” parties in Greece on Sunday, followed by the virtual implosion of the Greek state, whose coffers are nearly empty. The current economy minister says Greece has enough money to survive until July 15.

Source and read more at:

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/06/15/world/europe/europe-future/index.html?hpt=hp_c1

TBU NEWS