After some years of peace, the western Balkans are again descending into instability. Across the region, people are taking to the streets, demanding the resignation of governments. Thousands are fleeing abroad in search of jobs and opportunities. A violent strand of Wahhabism is taking hold among the region’s Muslim population. Perhaps most worryingly of all, the threat of disintegration is returning, as malcontent minorities try to divide their states.

Bosnia has long been the most dysfunctional state in the region, wasted by civil war in the 1990s and afflicted by ethnic divisions ever since. The Serbs and Croats have never abandoned their goal of separation. Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska (Bosnia’s Serbian “entity”), is being squeezed by political rivals at home and investigated by police in Sarajevo for alleged money laundering. To shore up his position, he has threatened a referendum on independence for Republika Srpska, scheduled for 2018.

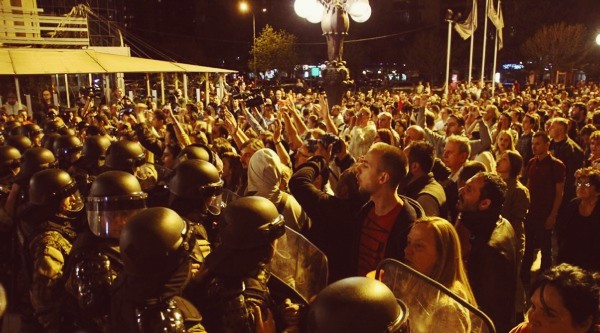

Not far behind is Kosovo, an impoverished plateau in the Šar Mountains. It is unrecognised by half of the world, run by a corrupt elite and saddled with an embittered Serb minority. After years of resistance, Kosovo’s Serbs have recently extracted the right to territorial autonomy from the country’s notional EU supervisors. This has provoked a ferocious backlash from Albanian nationalists, who have attacked the parliament and held a series of violent street demonstrations.

Meanwhile, Macedonia is in chaos following the leaking of tapes that led to accusations that the former prime minister Nikola Gruevski had spied on the population and had been involved in corruption, electoral fraud and outright criminality. This has outraged the unhappy Albanian minority, which blames its leaders for upholding an illegitimate government instead of its community rights. In response, this group is demanding the federalisation of the state, auguring its potential disintegration. In the Balkans, it all eventually comes back to nationalism.

While local factors go some way to explaining the turmoil, however, they don’t tell us why the region as a whole is experiencing such instability, or why events are turning for the worse. The key to understanding the malaise is to recognise the Balkans’ position as a borderland between great powers.

Indeed, many of the EU’s problems seemed to emanate from the Balkans. Most obviously, there was Greece’s mismanagement of its economy, which posed a mortal threat to the survival of the eurozone and, by extension, the EU. But as Europe descended into recession, the issue of migration from Bulgaria and Romania also became a crucial political topic – and remains so today, as migrants and refugees from the chaos in the Middle East use the Balkans as a conduit to Europe.

In this context, no one was surprised when, in 2009, the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, publicly concluded that the EU needed to pause its policy of enlargement. All of this had an impact on the region, which interpreted it as Europe’s drawbridge closing. To all intents and purposes, the EU had reneged on its bargain with the western Balkans, which traded the prize of membership for good behaviour. All that remained was the prospect that one day, years in the future, after multiple reforms, the states of the region might join the EU, if it was in any position to enlarge and if it even still existed.

This changed the balance of risks and opportunities for those aspiring to join. Why continue with reform, especially when this implied serious economic pain? Was the EU even a desirable place to be? Greece’s example was hardly encouraging, nor that of Croatia, which squeezed its way into the EU in 2013 only to become the new sick man of Europe. Then the UK began to consider exit – hardly a vote of confidence.

Across the region, the reform process slowed even further. States such as Macedonia and Serbia shifted their focus towards the emerging economies of Turkey, Russia and China. Internal stability began to decline, aggravated by the recession that the EU exported to the region. Albania, Macedonia and others experienced mass demonstrations. Separatists began to renew their challenge to the American-imposed order, led by the Bosnian Serbs.

This is not to say there hasn’t been formal progress towards joining the EU. In the past couple of years, almost every country in the western Balkans has taken a step closer. Bosnia and Kosovo have been offered stabilisation and association agreements, the first step on the road to membership. Albania has been recognised as an official EU candidate. Serbia has opened membership negotiations. Montenegro, the most advanced country in the region, has closed several negotiating “chapters”. However, this bureaucratic progress does not necessarily reflect progress on the ground – in some cases, it signifies the opposite.

More precisely, the integration process has become a pretence that suits all sides. The EU can pretend the project of integration continues even as the eurozone and migration crises rage. And regional governments can pretend they are steering their countries towards a better future, for which they are richly rewarded by Brussels.

It is possible that a tiny country such as Montenegro will scrape into the EU on the back of this make-believe and Serbia will make some progress. But for other Balkan states, their journey towards Brussels will be more like that of Turkey, the eternal European aspirant. In reality, the western Balkans is once again losing its mooring.

The waning influence of the West has created an opening for new external powers, such as Russia, which has adopted a more active policy in the Balkans since the onset of the “new cold war”. Unquestionably, Russia is now a major influence on the region, especially in the Christian Orthodox countries of Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, Bulgaria and Greece. But its most significant involvement is in Bosnia.

In the past couple of years, Russia has feted Republika Srpska’s President Dodik, shielded Bosnian Serbs from accusations of genocide, called for an end to international supervision and, if media reports are correct, encouraged Bosnian Serbs to press their demands for independence.

Russia is not overtly trying to overturn the regional order. Instead, its aim is to bolster its alliances, deter the expansion of Nato and defend its economic interests in the Balkans. But regional disorder could still be the outcome. If Russia is cornered by the West over Ukraine, Moscow could trigger a serious regional crisis that embroils the EU and Nato, simply by giving a green light to the Bosnian Serbs.

A domino effect would then take hold. The departure of the Republika Srpska would open up the question of Serbia’s borders and encourage Kosovo’s Serbs to separate themselves completely from their country’s Albanian population. This would provoke Serbia’s Albanian minority, who live in an enclave adjacent to Kosovo, to make a similar break from Belgrade. Macedonia’s Albanians would then try to separate from their Slavic compatriots, fuelling the creation of a “Greater Albania”. Bosnian Croats would seek to integrate their territory with Croatia. And many in Montenegro would seek close relations with an expanded Serbian state. The West would undoubtedly refuse to recognise any of this to prevent the onset of violence but the facts on the ground would speak for themselves.

Any new Balkan conflict would draw in a wider cast of players. Russia would not sit by and let others determine the outcome of events; too much is at stake. The plight of Muslim Bosniaks and Albanians would draw in foreign jihadists, as happened in the wars of the 1990s – only in much greater numbers, given the upsurge in Islamism in Europe and the Middle East.

Meanwhile, several EU states would struggle to avoid entanglement. Croatia, which has recently adopted a more nationalist posture, would inevitably intervene in Bosnia on behalf of the Croat population. Bulgaria and Greece would take a keen interest in the fate of rump Macedonia after the departure of the Albanians.

All this leads to a sobering conclusion. As the EU loses its dominance in the Balkans, so the region’s unresolved nationalisms are returning to the surface on a bed of popular discontent. The Balkans have the potential to blow their problems back into Europe, entangling the EU in a new, potentially violent regional crisis. This may not happen tomorrow but, as the EU’s influence wanes, the day of reckoning draws ever closer.

Source and read more: NewStatesman.com

Best Regards

TBU NEWS